A Commonplace Book originated from categorizing and taking down notes from what one reads, capturing quotes, images, and ideas. In contrast to a journal which is chronological, a Commonplace Book is categorical. John Locke wrote a book on how to keep a Commonplace Book, and writers like John Milton and Virginia Woolf organized their thoughts into such notebooks. Harvard has photographed Commonplaces dating back from the 16th century and in a variety of languages. Wikipedia describes Commonplace books, or commonplaces as,

a way to compile knowledge, usually by writing information into books. Such books are essentially scrapbooks filled with items of every kind: recipes, quotes, letters, poems, tables of weights and measures, proverbs, prayers, legal formulas. Commonplaces are used by readers, writers, students, and scholars as an aid for remembering useful concepts or facts they have learned. Each commonplace book is unique to its creator’s particular interests.

The term, however, grabbed my attention. Like Aaron Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man, the word “common” made me feel that this type of journal was ordinary and easy.

Everyone could create a Commonplace Book: A book that could account for everyone and contain anything and everything.

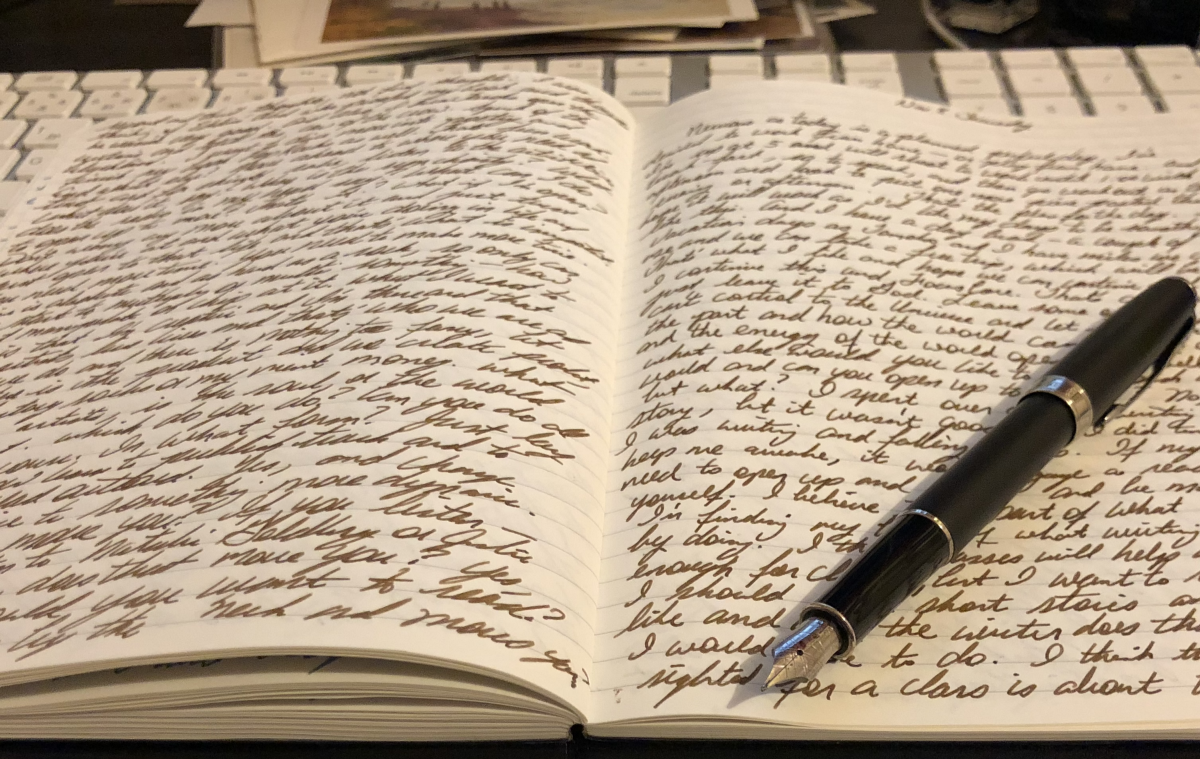

I took the meaning far from the note taking. A commonplace book, I imagined, is like an entrance ramp to the most democratic of entrances, encompassing the common daily sights, sounds, observations, and impressions of the everyday: ladybugs on a breakfast plate near the toast, the smell of diesel fuel from a bus on a cold winter morning, the sound of snow crunching under feet, the monumental complaints of the day, a shiver from a brisk North wind in November, a complaint about how my co-worker whistles out of tune, the calico cat that ran past, and the green glass jar that captured in the shop window. Nothing too important, but just little items that captured my attention. Of course, the commonplace book would be big enough to capture the heaviest of world changing ideas, thoughts, plans, lists of creative endeavours, sketches for how to build a deck in the back yard, poems, notes for a song, or letter ideas to a lover.

In contrast to the Commonplaces, the word “journal” sounds serious and stuffy. We keep a journal, the way that one “keeps” a pet, with some haughty connotations formed by published journals like “The Wall Street Journal,” “The Journal of Administrative Science,” or more extensive research based journals, like “The Journal of Investigative Dermatology.” A journal is for something important. Like a commonplace book, a journal may be a doorway, but it feels less accessible. Perhaps an automatic door where anyone can enter, but there is definitely a stairway leading up to the door. The proper attire for a journal is a black turtleneck sweater. The pages of a Moleskin qualify for a good journal — preferably unlined, with a few of the pages dogeared. The observations of the day, sketches perhaps taken from the Tate Gallery, a sonnet or two, and the outline for the latest novel.

Personally, I dreamed of having a journal that looked like Indiana Jones, tattered, worn, with maps, sketches, diagrams, secrets written in code. Or it could be like Da Vinci’s notebook with sketches, cartoons, and elaborate drawings scientific thoughts, dissections, wings of birds, flowing wind and waves, and the hands of people observed. I longed to write long, beautiful passages and draw simple sketches like Hendrik van Loon does in describing George Washington going across the Delaware and I would sketch him sailing on that cold morning. I wanted my journal to read like a book with delightful aphorisms, insightful or even crude drawings, and a joke or two.

Then in my dream, after I had long been dead and buried, all my tattered journals would be found by some future collegiate Freudian scholars writing their master’s thesis pouring ceaselessly over the pages searching for some deep insights. Or perhaps my progeny would seek for insights into their mysterious and quirky grandfather or great uncle, to find how he agonized over money or deeply loved my wife. The gentle secrets of my childhood might be revealed and occasionally, a sentence or two may inspire them. I wanted to fade into history while my journals proudly orate like the replicant, Roy Batty in Blade Runner, “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.”

Then there is a diary. Lovely little things. I picture Louisa May Alcott sitting at her writing table, selecting the images from her daily life, the weather and the scone she had for breakfast with a tad of marmalade recorded in the gentle, rounded letters, in the most clean fashion. In a diary, complaints about the cold, slip in nicely next to notes about a stranger who visited in his silk hat and calf-skin gloves that he removed and then lovingly caressed his brown, handsome mustache. A diary conceals the facts of the day, the implied urges of the writer, which in turn give future Freudians stacks of research to sift through. Or maybe a diary is a bit more whimsical, kept on the beside where sex and intrigued are recorded. Something Budget Jones would be proud of.

I got my first diary when I was very seven or eight. It was a red velvet book that snapped shut with a metal button. On the cover was written in gold, “Diary.” Inside, there was a “19___” where the year could be written in the year, along with the month and day. Then I could write along the gold lined paper with my favorite writing instrument was a BIC four color pen, which had: green, black, blue, and red ink. I fearlessly used all 4 colors, sometimes in the same entry. The letter shapes are shaky — the early attempts of cursive who has just learned how to connect all the letters together.

There was the day when I sneaked into Mom’s bedroom room, and on her nightstand, found her own diary. I opened it. Her words were scribbled in black felt pen. Her letters were round, neat, easy for my elementary school learning to scan. I don’t remember reading per se, but only searched for one thing: my name. All the other words didn’t seem important — her random thoughts, dreams, ideas, and struggles of life. Here and there were references to me and I could learn about myself, my mother’s secret thoughts about me. Then I found something that shocked me. She had been reading my diary. I slammed the book shut. I wanted to confront her. But because I was reading her journal, there was no real way for me to confront her. So I kept my secret, and whenever I wrote in my journal, I guarded what I wrote. I had discovered the importance of having a reading audience, even when we believed we were writing only for ourselves.

The connotation of diary holds too many secrets.

Now, I sit in my office typing on my Mac. I found a great little App called “Day One,” where I can scribble down an entry — my electronic Commonplace book that works on my mobile phone and tablet. People think I’m texting or responding to email, but in reality, I’m jotting down scenes and thoughts, ideas, and dreams. Thirty years ago, I carried a pocket notebook and tiny pen ballpoint pen the size of a toothpick around with me anywhere. With the joys of technology, it’s much easier to jot down ideas anywhere and at anytime.With a computer or tablet, I can type or dictate everything. Then cut, paste into a blog, essay, or story. I had a writing friend who told me that writing on paper is writing with earth and stone (paper and pen), versus writing on the computer is writing with light. The nature of the tools allow for different dynamics. Myself, I compose stories with the computer. Poetry and essays I always do my first draft in pen and paper. There are no hard or fast rules, though, and I change with my interests. I’m in a transition shifting back into using notebooks more and more — going analog. In primary school I wrote a diary, and then I graduated to a journal. In University, I found Julie Camron’s Morning Pages: 3 pages of long-hand written out. I was religious in writing every morning. I would roll out of bed, regardless of the time or temperature and write. If I had to take a plane at 5:00 a.m., I would wake at 4:30 to write. I wanted to recorded dreams, feel in flow, and experience synchronisty. Then I found Natalie Goldberg’s Writing Down the Bones. She described writing like meditation, thoughts flowing on the page. Next, came Stephen King’s idea from his excellent book, On Writing, where writing is “telepathy, of course.” He explains how as a writer in his time and place can connect to the reader in her time and place.

various colors of inks I like to use

All these combine for me into a friendly Commonplace Book, or CB for short.

A CB is a friendly, casual place to relax, to scribble, journal, record events, meditate, and connect to our future selves.

The notebooks are random, messy, comfortable like an old pair of jeans, a warm sweater, or silk pajamas. The majority of the words scribbled are messy, even sometimes illegible. There are ideas, but not life changing. They don’t need to be. They are a place to relax. They may be lights in the night sky, but I don’t expect them to be planets or moons. There is nothing about them but gibberish. That’s okay. They are just common. They are common place for a common person, just as the stars are common. It is always good to remember that each star is a sun’s chance to shine, just as each common word and thought is a unique chance for us to capture and realize our life and share our thoughts. The point, though, is to take those common ideas, and then create a spectacular life with extraordinary works.